As market turmoil and volatility continues at home and abroad, the economic landscape for investors seems to be ever-shifting. Between the raging inflation in the U.S. economy, the corresponding rate hikes from the Federal Reserve, and consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth, the uncertainty of where markets and the global economy may head is particularly acute. For those investing in not just foreign assets but also domestic securities, it may be essential to understand the interrelated effects between asset prices and the value of the U.S. Dollar. As inflation has raged in the United States, the Fed has raised interest rates in large steps, so as a result, over the last year, the Dollar has seen an unprecedented bull run not seen in nearly a generation. So today, we take a deep dive into where the U.S. Dollar may go from here and how some investors are seeking to position themselves in response.

A Brief Lesson in Macroeconomics

Understanding the dynamics between the U.S. Dollar and various asset classes, helps to understand what metrics drive the value of a currency. As many of us remember from Econ 101, the currency is a medium of exchange to engage in economic activity. From the days before the invention of money, commerce was conducted mainly via bartering: I will trade you one bushel of corn for one cow.

But let’s say the herder you’d like to acquire a cow from does not need corn and is instead looking to trade for a bushel of wheat – you would first have to find a farmer willing to trade his wheat for your corn, then go back to the shepherd and trade for his cow. With the invention of money, a currency mutually agreed upon within a society facilitates economic activity by forgoing the multi-step process needed to exchange goods and services. At a basic level, the foreign exchange market operates similarly. In the United States, our medium of exchange is the U.S. Dollar, and so for those seeking to purchase goods and services or make investments in the U.S. economy, much like the farmer who first needs to trade corn for wheat, and then wheat for a cow, a foreigner investing in the U.S. must first exchange his currency for the Dollar, and then trade his dollars for the asset he’d like to acquire.

So what drives the value of the dollar? At a fundamental level, like all economic transactions in a free market, the strength of the Dollar is driven by the relationship between the demand of those holding foreign currency to invest or purchase goods in the U.S. economy relative to the available supply of those Dollars. Aside from the aggregate of economic activity itself, the Federal Reserve is arguably the most significant influence on the demand and supply side of the equation of the U.S. Dollar. The Fed has what is called a dual mandate of “full” (or “maximum”) employment in the United States and low-and-stable inflation, which it achieves through a variety of tools, most notably through its manipulation of interest rates.

In times of economic distress, the Fed typically lowers interest rates to make borrowing money cheaper and, therefore, easier for consumers and businesses to purchase things and make investments; meanwhile, the reverse is true when the Fed seeks to cool down an overheating/inflationary economy, and as a result, will raise interest rates to curb economic activity. However, as interest rates in the U.S. increase in relation to those in other countries, foreign investors’ ability to invest in the American economy becomes relatively more attractive as the risk-free rate rises, increasing demand for the dollar. Simultaneously, because the goal of interest rate hikes is to reduce the supply of money and economic activity on the supply side of the equation, fewer dollars become available for foreigners to acquire.

How Inflation Has Led To A Strong Dollar

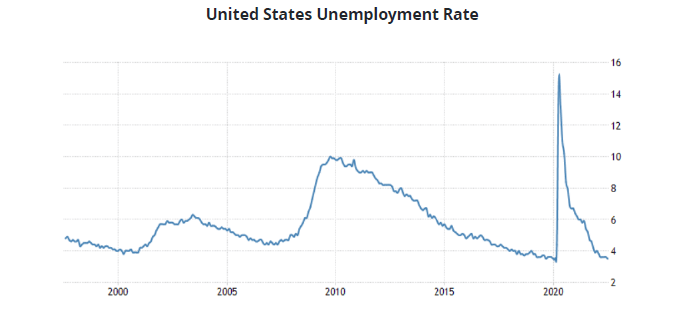

In response to the highest inflation in a generation and a half, the Fed has thus belatedly begun a series of interest rate hikes to make borrowing more expensive and curb economic activity. With unemployment running near historic lows, the Federal Reserve is said to be less concerned with the employment side of its mandate and hyper-targeted at returning the economy to low and stable inflation (typically defined as ~2%)

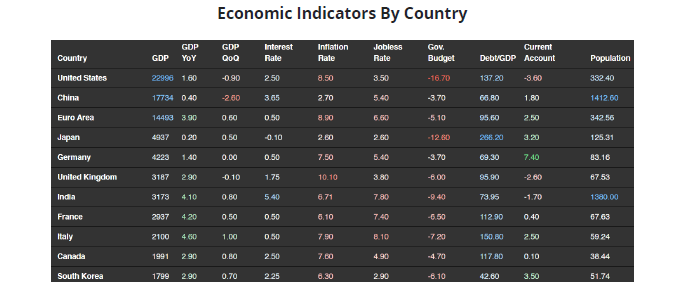

As a result, the Fed’s rate hikes, now hovering at ~2.50% and forecasted to continue to rise, have invested in the U.S. economy, relative to when the risk-free rate was maintained at 0%, more attractive. And especially relative to those of other Western and Developed countries, the United States currently stands tied with Canada with the highest overnight interest rate:

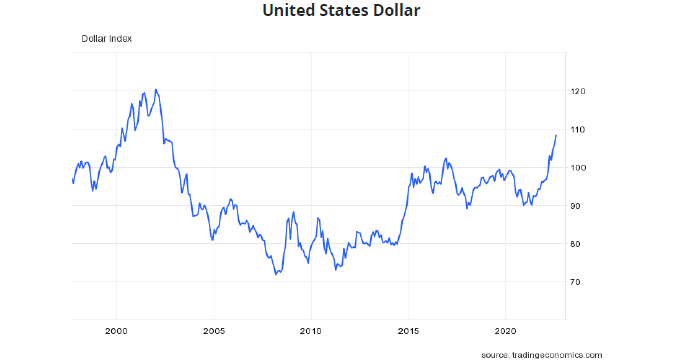

While, by definition, inflation erodes the value of a currency, the market’s faith in the Fed to defeat the recent bout of accelerating prices through aggressive rate hikes has outweighed the effects of inflation. In turn, the Dollar Index – which represents the value of the dollar relative to a basket of six foreign currencies that represent some of the largest developed trading partners of the U.S.: the Euro, Swiss Franc, Japanese Yen, Canadian Dollar, British Pound, and Swedish Krona – has reached its highest level in 20 years:

Where Will a Strong Dollar Go From Here, and How Could it Affect Investors?

While it is impossible to predict where a currently strong U.S. dollar will go from here, two dynamics to watch for are, first, the inflationary environment and, second, GDP growth. In a situation where inflation expectations well exceed the Fed’s 2% target, owing to the ability of runaway price rises to cause a snowball effect of erosion in the faith of an economy, the Fed has historically responded with less concern for keeping GDP growth high than with curbing prices. As of the New York Fed’s latest survey, consumer expectations for inflation – a key metric the Fed looks at in determining rate hikes – indicate that the Fed should accomplish its goal of achieving its ~2% goal within five years. Were this to bear out, according to the Fed’s most recent minutes, rates should top out in the 3% range. However, were inflation to continue raging, the Fed has likewise indicated an appetite for further hikes beyond those already forecasted. Were either scenario to come to fruition, all things held equal, the dollar is likely to continue rising in value. However, such scenarios never play out in a vacuum. And there is also the dynamic of GDP growth – as we saw following the rate tightening cycles of the 1980s, if the Fed is overly zealous in raising rates, economic activity may collapse, which could lead to an acceleration of rate cuts, and in turn a weakening of the dollar in the short-to-medium term.

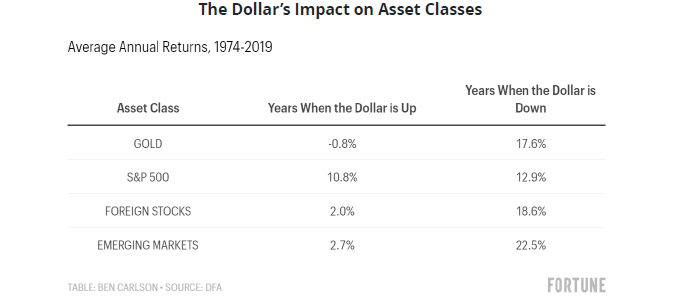

Although it is impossible to know which direction the economy will head (as we’ve learned several times in recent history after the shocks of the COVID-19 pandemic and the War in Ukraine), there are several asset classes with stronger correlations to the dollar than others. Historically, research shows that assets like commodities, particularly precious metals like gold, international equities, and export heavy industries all respond very heavily to moves in the dollar:

Given the potential for future stagflation, particularly after two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth, it may be difficult to predict how various asset classes will respond. For example, commodities, most of which are denominated in U.S. currency, typically drop in price in response to a strong U.S. dollar. However, owing to the shock of the war in Ukraine and continued supply chain bottlenecks, we have seen the opposite scenario. Likewise, export-heavy industries like defense historically outperform when the dollar is weak, as foreign nations can afford more heavy weaponry. Yet, we are also seeing the reverse, with companies like Lockheed Martin heavily outperforming broader U.S. Equities. Floating-rate bonds, however, have continued to hold up, buoyed by rising interest rates.

As a result, rather than attempt to navigate an incredibly complex macroeconomic situation, some advisors and their investors may be better equipped by leaving the day-to-day trades and rebalancing to the types of managers who are keenly familiar with the space and have shown the ability to navigate these types of generational events. Some strategies at the top of the list are global macro funds, but multistrategy and equity market-neutral managers on the hedge fund side are also worth looking at. Moreover, private credit strategies, which typically invest in floating-rate debt, may be a solution for those seeking a fixed-income replacement but struggling to find a suitable domestic or international option. Advisers should understand such strategies’ risk-return profiles in determining whether they are ideal for their investors.

Conclusion

With a uniquely complicated economic environment, a strong U.S. dollar in the face of war, inflation, rising rates, and a potential recession looming, the U.S. and global economies are surfacing for a once-in-a-generation dynamic. While many advisors may struggle with making the right investment decisions in the wake of these complex and hard-to-predict environments, a variety of hedge fund and private market strategies may be a solution. Rather than trade around a strong U.S. dollar themselves, an allocation to hedge fund strategies like global macro, multistrategy, and equity market neutral, as well as private credit and venture capital funds with large foreign budgets (mainly while valuations abroad are cheaper in dollar terms), may help advisors better tackle the markets.